Was this man my Great Great Great Grandfather?

For may years I thought that my Great Great Grandfather, James Henry Coventry, was the son of William James Coventry and Ann Lucas. After many years of research I have still not found proof of James’ parents. However, increasingly I think it is more likely that James was the son of William James’ brother, John Coventry. In particular, a couple of years ago I came across a report of William James’ death that listed his children – and James Henry was not amongst them!

Given a body of circumstantial evidence suggests that James is connected to this family, it seems that his father was probably the other son, John. Unfortunately it has been difficult to discover much about John and even more difficult to learn anything about his wife, Rachel Ward. Their children have also proven difficult to trace.

Watch out for other Johns

To add to the confusion, William James had a son named John Francis, born in 1840, so it can be difficult to tell whether news reports and other documents about ‘John Coventry’ refer to the uncle or the nephew. I have recently discovered that John Francis died in New Zealand in 1930 and his death certificate tells us that he had lived there for 55 years, suggesting that he arrived there around 1875. However, as the older John died in 1867 this new information does not do a great deal to sort out the confusion.

There was also a convict, John Coventry, who arrived aboard the Moffatt in 1837. He was born about 1810, so six years older than the man I am researching.

So what do we know about John?

Recorded as ‘John’ in Knopwood’s Hobart Town baptism register, we know that he was born on 9 February 1816 and baptised on the 15th of March. His mother’s name was Mary Martin and she was not married to John’s father. However, we also know that John was the fourth of four children that Mary had while she was living with William Coventry, a convict from County Donegal in Ireland who had arrived in NSW aboard the Hercules in 1802. William was sent to Norfolk Island where he probably first met Mary Martin, the daughter of First and Second Fleet convicts, Stephen Martin and Hannah Peeling. Some 17 years younger than William, and only fifteen at the time, Mary appears to have been living with or married to John Bentley at the time she left Norfolk Island (as part of the Government’s planned closure of the first settlement) in May 1808. William had departed on board the Lady Nelson a few months earlier, arriving at Hobart Town on 14 February 1808.

On 16 April 1811, Mary Martin baptised her first child, Margaret. Like John, and her other siblings, the baptism record makes no reference to William Coventry but each of the children grew up using William’s surname. Another girl, Catherine, was baptised on 23 December 1811 (suggesting Mary was already pregnant, and perhaps that Margaret was already a toddler, at the time of the April baptism). The most well-documented of the siblings, first son William James was born on 1 January 1815 and baptised by Reverend Knopwood on 16 March.

The Coventry family lived on a 52 acre land grant at Back River (now Magra) in the parish of Melville, near New Norfolk. William grew wheat and potatoes and provided fresh meat to the Government’s stores. No doubt the children helped on the farm from a young age.

Without going into all the details of William’s story in Van Diemen’s Land, it seems that there were several brushes with the law before the awful events that would leave John and his siblings fatherless. In June 1816, when John was just a few months old, his mother had the worry of wondering what would happen when William was charged with harbouring an Irish convict, Thomas Kelly, who had escaped from a gaol gang. William was charged 40 shillings as surety for twelve months good behaviour. In 1827 he was similarly fined (this time fifty one dollars) for harbouring Robert Briggs, a runaway from the service of Abraham Walker. Worse was to come though, when in May 1829 William was tried at the Supreme Court, along with several others, for stealing three bullocks, the property of the late Daniel Stanfield.

John was only thirteen years old when his father was sentenced to the horrifying prospect of seven years at Macquarie Harbour. His sisters Mary and Catherine had married the year before and already had young children. Inexplicably, the records suggest that Mary Ann Martin (using her earlier married name, but spelt ‘Beatley’ this time) married her neighbour, Francis Cox, in February 1829, some months before William’s exile. But can this be right? Francis’ first wife, Sarah, was still alive (she died in 1832) although there are newspaper reports from 1825 indicating that she had deserted him. All of this needs more research, but in any event, it would seem that John’s family life was far from calm and serene. It is not clear when Mary and William’s relationship folded, nor when Mary actually began living with Francis but it would seem that some time around the time of their father’s departure William Jnr and John Francis acquired a step-father and step-siblings. And what, I wonder, happened to the proceeds from Coventry’s farm, which was auctioned just weeks after William’s conviction?

News of his father’s escape … and horrific death

In November 1830, the Hobart Town Courier published a fascinating story told by two escapees from Macquarie Harbour. The article mistakenly refers to Thomas Coventry but it is clear that this is about William. I wonder how the news was broken to Mary and her children?

Five men lately absconded from Macquarie Harbour, two of whom only succeeded in arriving at the settled districts, after a journey of 18 days through the bush. They state that two of their companions (Richard Hutchinson, well known in the colony by the name of ‘Up-and-down Dick’, and the other Thomas Coventry, formerly proprietor of a little farm at the foot of the Dromedary, known as ‘Coventry’s point,’) were left behind, after being with them for six days, as they could not swim across a river, and that the remaining three, Edward Broughton, Matthew McAvoy, and a man named Fagan, continued their route until within about 4 days before the survivors were taken — when Fagan, who was very much exhausted, being unable to run from a tribe of natives whom they fell in with, was killed by them.

These men have been closely examined in the gaol by Mr Mulgrave, the Chief Police Magistrate, respecting the fate of their comrades, about which mystery hangs.[1]

What rumours and speculation must have followed before the macabre truth was revealed in the colonial newspapers some nine months later? When did William’s family learn of Broughton’s confession confirming not only that William was dead – but cruelly murdered and eaten by his fellow escapees – and worse, that he too was accused of feasting on the flesh of the first of the escapees to have been murdered, Richard Hutchinson. The confession is lengthy and makes gruesome reading.[2] Broughton says that they were starving when they killed Hutchinson but not when they killed William. Having murdered Hutchinson they had become afraid of each other and could not rest. William saw Fagan approach him with the axe and begged for mercy; the first blow did not kill him and Macavoy and Broughton ‘finished him and cut him into pieces’. How dreadful it must have been for Mary and the children to hear of this confession and to see it broadcast about the colony. I wonder whether they were witnesses to Broughton and Macavoy’s executions on Friday the 5th of August 1831?

Marriage

How all of this affected John we can only imagine. Unfortunately he leaves a very slim footprint in the records of the day; perhaps not surprising given the relative remoteness of Back River at the foot of Mount Dromedary. John married Rachel Ward at St David’s in Hobart on 18 December 1843. Unfortunately all we know from the register is that twenty-seven year old John was a farmer and bachelor and neither he nor his wife, eighteen year old Rachel Ward, could write. The marriage was conducted by the fire and brimstone preacher, Rev William Bedford; the same man who had heard Broughton’s confession and delivered the sermon at his execution. The wedding ceremony was witnessed by the clerk, James Sly, and John Everett, who I am yet to identify.

Rachel Ward has proven even more elusive than her husband. There were Wards in Hobart and at Circular Head, where the married couple were to move, but so far I have learnt nothing more about Rachel. I haven’t found her amongst the Tasmanian convict records or the less comprehensive records of free arrivals and state registered baptisms.

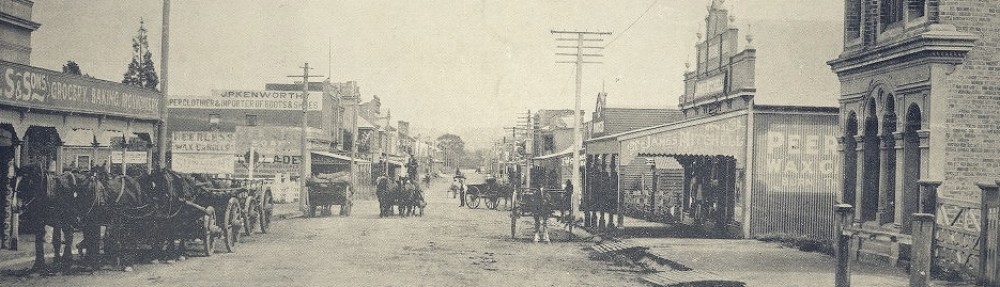

Circular Head

A brief reference to John Coventry in the shipping news a week prior to his marriage suggests that he may have been farming in the Circular Head district or, perhaps, checking out the prospects for establishing his family home in this expanding district.[3] And, just days after his wedding, John was to return there, apparently without his new bride, aboard the Eagle which carried goods and passengers between the settlement and Launceston.[4]

It seems likely that, together with his brother William, John had responded to the Van Diemen’s Land Company’s advertisements, appearing in 1842, for blocks of land on seven year leases at 2 shillings an acre. The terms of the agreement provided that the first three years of rent were to be spent on improving the land with the remainder to be paid to the company in cash or produce. At the end of seven years the tenant could either purchase his farm at £2 an acre or surrender it back to the company and be paid £4 for every acre under cultivation. To make the offer even more attractive, the Company’s chief agent, James Gibson, undertook for the Company to buy all the tenants’ produce for seven years at fixed prices for potatoes, barley, wheat and oats.

Children

I haven’t been able to discover when Rachel joined her husband but on 23 October 1844 the couple’s first child, Mary Ann, was born and her birth subsequently registered in the district of Horton, which included the settlements at Circular Head, Woolnorth, Emu Bay and Table Cape in Van Diemen’s Land’s far north west. Coincidentally, on the same page of the birth register is the registration of a son born to VDL Company Commissioner James Gibson. Mary Ann was baptised into the Church of England on 10 November 1844.

On 1 March 1846, John and Rachel welcomed their first son, also named John, into the world. He was baptised three weeks later, on 22 March 1846. His birth registration tells us that his father was a farmer at Duck Bay, Forest, Circular Head.

In quick succession, another son, William Thomas Coventry, was born on 29 June 1847 and baptised on 25 July.

The fourth and last child registered to John and Rachel, and possibly my Great Great Great Grandfather, was James Daniel, born on 10 November 1849 and baptised on the 26th. Could he be my James Henry Coventry?

This document is the last reference I have to Rachel Coventry. She was only 24 at the time and in this era of large families it is unusual for there to be no more children born to this couple. I wonder whether Rachel died soon after James’ birth, or perhaps during a fifth pregnancy? Or was hers one of the marriages that could not survive the hardships of pioneer life? Any clues would be very welcome.

Many years ago I came across some of the Van Diemen’s Land Company records at the National Library. They were on microfilm and are both poorly referenced and difficult to read (particularly, it seemed, whenever I might expect to chance across a Coventry, Lucas or other family name). Unfortunately the information I retained is fairly sketchy but there are a few small clues relating to John and his family.

A record from 1848 showed that Mary Ann, then aged 4, was admitted to the Forest School. She attended for sixteen days then left on 26 January 1849. On 9 July she was admitted to the Stanley school. Again, she only attended briefly – 18 days in that quarter. In January 1850, Mary Ann was readmitted, along with her brothers John, then aged 4, and three year old William. In the quarter to 31 March 1850 they attended for 17, 19 and 13 days respectively. Hard to imagine these tiny children traipsing off to school at such a young age.

Another glimpse into family life is provided by local church records. For example, on 8 May 1848, John and Rachel attended the recently completed St Paul’s church at Stanley where they were witnesses to the marriage of their friends Samuel Horton and Margaret Smedley. Samuel had only been in the colony seven years, having been transported for housebreaking in 1841. He appears to have arrived at Circular Head around October 1847. Margaret’s family had been at Circular Head since about 1842, around the time the Coventry brothers took up their land.

Farming for the Van Diemen’s Land Company

One of the VDL Company documents lists tenants renting land at Forest. Unfortunately it is not dated but it does list John amongst the debtors to the company, together with his brother William and William’s brother in law, John Richard Lucas. At the time William had cleared more than 36 acres of land, John had cleared 16 and J R Lucas, 20. Later, in 1849, there is a very difficult to read document which releases John from some of his debt because William had, for the sum of £34, taken over the block.

Sadly, it seems that John’s luck was only to worsen. In May 1850 the Launceston Examiner reported on the loss of the Coventry brothers’ boat, The Struggler:

Wreck — A cutter of about twelve tons, named The Struggler, was lost at the River Forth, on the night of Wednesday week, 24th April. The little vessel was the property of two brothers named Coventry, by whom she was built at Circular Head. She was on her way to Launceston to be registered, when, it coming on to blow, the persons in charge mistaking the Forth for Port Sorell, ran in and struck upon a reef. The owners have thus sacrificed their all, and ten tons of potatoes, put on board for Mr Tyson, have been lost. The wreck has been purchased by Mr John Williams for £12.[5]

The loss of their boat may well have been the straw that broke the camel’s back for the two brothers. While William was ultimately to return to Circular Head, in 1853 he moved his family back to Brighton in the colony’s south.

And there remains only fragments and snippets

From this point it is very difficult to know what happened to John and his family. Some of what follows may relate to my John or to another. It’s mainly snippets and speculation so any additional information or new hypotheses are very welcome!

A John Coventry appears as a witness in a Supreme Court case in 1851. He is living in Launceston, three quarters of a mile from Guests public house which was on the George Town Road. The 1856 Assessment Roll for Launceston lists a J Coventry at Cameron Street (which intersects with what appears to be the old George Town Road).

Things become interesting in February 1861 when the following advertisement (sometimes with slight variations) appears at least half a dozen times in The Cornwall Chronicle:

FIVE POUNDS REWARD — Absconded from the service of the undersigned, whilst in charge of a bullock team, laden with stores, after having stolen or disposed of the stores, JOHN COVENTRY, a native of Tasmania, stands about five feet six inches high, light complexion, sandy whiskers, stout made, very round shouldered, rather stiff in one knee — was of late years employed splitting on the Tamar, and boating timber to Launceston. His parents kept, or formerly kept, the “Crooked Billet” in Hobart Town. His wife and family reside in Launceston, and he has relations at Circular Head. He was last seen at Wheeler’s public house, at Cressy, where he staid [sic] from Thursday the 17th, until Sunday, the 20th instant; when he left his team, which he abandoned in Archer’s Forest. Any person giving information, which will lead to the apprehension of the said John Coventry, or which will lead to the discovery of the party receiving the goods, shall be paid the above reward. W Wilson, Cleveland. Feb 2.[6]

All I have is circumstantial evidence, but its worth unpacking this a bit. There is no earlier reference to John being employed as a splitter but this is certainly a skill that would have been useful in establishing his farm at Circular Head and probably in the early days at Back River. We can surmise from The Struggler article that John was involved in sailing or shipping goods from the north west to Launceston. And it is also true that his step-father, Francis Cox, was the licensed innkeeper at the Crooked Billet. It’s likely that his mother worked there too. It is also likely that he still had relatives at Circular Head as some of William’s children appear to have either stayed or returned there. His own children ranged in age from seventeen to twelve so it is quite likely that they were at still living at home (wherever and whoever that was with).

Interestingly, in the same month a death notice is published in the Cornwall Chronicle:

DIED — On the 9th inst, at Victoria, Mr John Coventry, late of Launceston, aged 44 years.[7]

There is no corroborating record amongst the Victorian death registrations or elsewhere, as far as I have been able to discover. Perhaps John was trying to cover his tracks or perhaps the notice genuinely relates to another John Coventry. There is a further possible explanation … read on!

I have found nothing more about John until his death is registered in the district of Horton in 1867. The registration tells us that John Coventry died on the 27th of January 1867, aged 51, of consumption. His occupation is again listed as splitter and the informant is his nephew, John (William’s son), a farmer at Forest.

Clearly there is much more to discover, although I seem to have hit brick walls in all directions. What happened to Rachel? and what happened to the children? Surely one of them married? Why are there no death records? Did they emigrate? or change their names? Did James Daniel become James Henry?

And who is Eliza Coventry?

In 1875 the Sydney Morning Herald carried this curious advertisement under the heading ‘Persons advertised for’:

If this should meet the eye of ELIZA, the wife of the late Mr JOHN COVENTRY, of Circular Head, she will hear of something to her advantage by sending her address to C. C., Solicitor, Tasmania.[8]

The obvious conclusion is that John has left property and fortune to Eliza but to date I have found no record of a will (let alone of a marriage to anyone called Eliza!).

Searching for Eliza leads to an extraordinary case of alleged kidnapping. While well reported in various newspapers I have not been able to discover what happened after the case was heard, nor prove the identities and connections of the individuals involved. But there are certainly potential connections to John and his family. Equally, there are many statements presented as facts that I have not been able to corroborate, as well as some fairly obvious lies. Here is the story as it appeared in The Argus on 13 January 1870.[9] The italics are my commentary, the bold, my emphasis.

EXTRAORDINARY CHARGE OF KIDNAPPING. At the City Court yesterday (before Messrs Panton, MP, Call, Rawlings, King and O’Brien) Eliza Coventry, late of 45 Lygon Street, Carlton, a well-dressed woman, of respectable and prepossessing appearance, and apparently about middle age, was summoned on a sworn information by Mary Ann McCarthy for having on the 25th November last unlawfully by force taken away a female child, to wit Annie Eliza, seven years of age, with intent to deprive Mary Ann McCarthy, the mother of the child, of the possession of the said child.

Could this be Eliza, wife of John Coventry? and his daughter Mary Ann (now 26 years old)?

The complainant was a woman of small stature, but rather good looking, and of somewhat Jewish cast of countenance. There was a considerable likeness between the complainant and the defendant, who was her mother.

This presents a problem to my theory, unless the reporter is mistaken or Eliza and Rachel are the same person?

The complainant, Mary Ann McCarthy being sworn, stated — I am the wife of Robert McCarthy, residing in Oxford Street, Collingwood. On Thursday, the 25th November last, I and my husband were out, and on returning were told by our son, a child, that his grandmother, the defendant, had been to the house and take our other child, Annie, aged seven years, away. My name was Coventry when the child in question (Annie Eliza) was born, and I was then living at Launceston. My mother had the child registered in Launceston under the name of Anderson, without my knowledge, and the child was known then as Annie Eliza Anderson. Mr Sams was the father of the child, but I did not receive any maintenance for it. The birth of the child was concealed by my mother. There was no doctor at the birth of my child, which was born in my mother’s house, at Tamar-street, Launceston, on the 24th October, 1862[10]. Some hours after I had delivered of the child, which was a girl, my mother told me to get up, and show myself to a man named Anderson, who was about the house, and a frequent visitor. I did so, while my mother went to bed, where she remained for three or four hours while Anderson was at the house. To my knowledge Anderson paid money for the support of the child, and sent some after he discontinued visiting my mother. Before the child was born, mother was in the habit of dressing so as to appear stout. No one was in the house but my youngest brother James at the birth, and I was only assisted by my mother. I nursed the child until it was about two years old. About a fortnight after my confinement I went to the registry office, and Mr Cathcart[11] looked up his books, and showed me the registry of a child purporting to be the daughter of Eliza Coventry and William Anderson. Nearly two years after the child was born, while I was nursing it, I went with my mother to Table Cape, Tasmania. The reason that my mother told Anderson the child was his was in order that he should marry her, though her husband was then living. While I was at Table Cape my mother took the child and kept it at Launceston for about seven months and when I went back to Launceston I found my mother living with Anderson. I remained there about three months. About three years after the child in question, which was my first, and while still living in Launceston, my second child, a boy was born, the birth being duly registered in Launceston. [No registration found.] In 1866 I came to Melbourne, leaving the two children at Launceston. I did not see them again until six months ago, when my mother came to Melbourne and brought the two children with her to Bouverie-street, Carlton, where I was living. After remaining with me about a month, she left, taking my girl (the child now in question) with her. About the 21st of November last my boy went to mother’s place and brought back his sister, who had black and blue marks on her back as if she had been beaten with a cane. I had not seen the child for two years and ten months up to six months ago, during which time my mother had the child, and I repeatedly sent money for the child. The child was only with me in November, from the 21st to the 25th. After my mother had take it away, I saw the child at Footscray on Tuesday, the 11th inst., when I served mother with the summons on which she is now before the court. The child had a peculiar brown raised mark on its right side, by which it could be identified. My mother was cohabiting with several men, and took the child to Weston’s opera house every night, and it is on account of the way she was bringing the child up that I want to take it from her. My little boy told me he had seen her in bed with a billiard-maker who belonged to the Globe Hotel, and I watched her conduct afterwards, and from what I saw was anxious the child should not remain with her. (The defendant here ejaculated that a daughter ought to be ashamed to speak like that of her mother.) Before the child was born my mother gave me to understand that the birth would be concealed. When the child was taken away on the 25th, my mother said that she would bring her back, and she brought her to the house in the evening, but took her away again, saying she would send her back next day, but she has kept her ever since.

The defendant stated that the child was hers, and not her daughter’s, but that she had no witnesses here to prove it being a stranger in Melbourne, or she would not have been treated in the way she had been. She further stated that the man who was living with or married to her daughter, and who was in the court, had threatened to “follow her to the gates of hell,” and that she was afraid he would do her some injury.

The Bench postponed the case until next day, in order that some inquiries might be made; also telling the defendant that she must summons the man referred to if he threatened her.

The next day, The Argus reported:

Eliza Coventry was summoned for unlawfully taking a child out of the possession of the mother; but the case was dismissed, being out of the jurisdiction of the Bench.[12]

Frustratingly, I have been able to verify very few of the facts. Nor have I been able to track down any original court or police documents. The court hearing was reported in various newspapers, with some points that go beyond or contradict The Argus report listed below:

- The Newcastle Chronicle reports that the son was born two years (not three) after the daughter. It notes that both births took place before Mary Ann’s marriage (which occurred after she arrived in Victoria in 1866).[13]

- The Newcastle Chronicle also states that Mary Ann did not know her age, but her mother told her she was fifteen when the first child was born [making her a bit younger than expected – 15 instead of 18].

- Of particular interest, The Newcastle Chronicle states ‘Witnesses’ father had left her mother long before. He was still alive, but her mother published an advertisement of his death in the papers, knowing well enough that he lived.’ Does this explain the 1861 death notice in the Sydney Morning Herald?

- In re-stating that the child did not belong to Eliza, Mary Ann said that ‘Her mother’s youngest child was now over twenty years of age.’ This is consistent with James being nearly 21.[14]

- The Launceston Examiner elaborated a little on the second day’s proceedings, reporting that ‘… Mr Panton, the Police Magistrate, told the complainant, Mary Ann McCarthy, that he was sorry he could not assist her, as it was beyond the powers of the magistrates to order the child to be given up to her, and that the best thing she could do would be to take the proceedings in the Supreme Court for the recovery of the girl. The complainant stated that the defendant (her mother) had got married only a few days ago, and had told the clergyman that she had only two children. The defendant stated that she had married for protection, and to get a home for the child in question, whom she still claimed to be her offspring, and not her daughter’s. She repeated that she was afraid of the man who was living with, but who, she alleged, was not married to her daughter, and said that she could not condone his faults as she had her daughter’s, though she would have done so had he been married to her daughter.[15] [I have found no registration for Mary Ann’s marriage to Robert McCarthy.]

- Commenting further a few days later, the Launceston Examiner opines that: ‘Plainly there has been perjury on one side or the other, and it will be a pity if the guilty party goes unpunished. A woman who would not hesitate to swear to a child being her own while it is another’s, would not hesitate to swear the paternity of a child upon any man she might think fit to accuse. But supposing the child to be Mrs Coventry’s, the motive of the daughter in seeking to take the child away from her seems inexplicable unless out of some spite; and it would be carrying spite to rather an extraordinary length to lay claim to an illegitimate child, with a view to bringing it under her lawful husband’s roof.[16]

So … intriguing, frustrating and not much closer to determining whether John and Rachel’s (or should that be Eliza’s) youngest son is indeed my ancestor. Adding speculation to speculation, if the story above does relate to ‘my’ John Coventry, it may well help explain why James is described as having ‘just turned up in Latrobe with no-one knowing where he came from’.[17] But there are many questions yet to answer!

[Added 22 August 2104]

Online resources

John Coventry on my Ancestry Tree

Notes

[1] 1830 ‘The Courier.’, The Hobart Town Courier (Tas. : 1827 – 1839), 27 November, p. 2, viewed 16 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4206106

[2] 1831 ‘EXECUTION.’, Colonial Times (Hobart, Tas. : 1828 – 1857), 10 August, p. 3, viewed 16 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article8646019

[3] 1843 ‘Shipping Intelligence.’, Launceston Examiner (Tas. : 1842 – 1899), 13 December, p. 5 Edition: EVENING, viewed 16 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36235427 – John Coventry is listed as a passenger aboard the Eagle, departing Circular Head.

[4] 1843 ‘SHIP NEWS.’, The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tas. : 1835 – 1880), 23 December, p. 2, viewed 15 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66015900 – John Coventry is listed as a passenger aboard the Eagle, for Circular Head.

[5] 1850 ‘Miscellaneous.’, Launceston Examiner (Tas. : 1842 – 1899), 4 May, p. 6 Edition: MORNING, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36265883

[6] 1861 ‘Advertising.’, The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tas. : 1835 – 1880), 16 February, p. 7, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65572611

[7] 1861 ‘Family Notices.’, The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tas. : 1835 – 1880), 20 February, p. 4, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65570462

[8] 1875 ‘Advertising.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 23 July, p. 1, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13357541

[9] 1870 ‘EXTRAORDINARY CHARGE OF KIDNAPPING.’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 13 January, p. 6, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5809902

[10] The closest registration I have found is for an unnamed female, born 30 October 1862, registered 24 November, to William Anderson and Eliza Anderson, formerly Frazer. W Anderson of Brisbane Street, an Uncle, registered the birth. I have found no record of their marriage, nor of any other children born to this couple.

[11] Mr George Cathcart held the position of Registrar of Births, Marriages and Deaths at Launceston but, according to his obituary, he retired in 1860.

[12] 1870 ‘POLICE.’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 14 January, p. 6, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5809978

[13] 1870 ‘A. VERY CURIOUS CASE AT MELBOURNE.’, The Newcastle Chronicle (NSW : 1866 – 1876), 20 January, p. 2, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article111157544

[14] 1870 ‘A. VERY CURIOUS CASE AT MELBOURNE.’, The Newcastle Chronicle (NSW : 1866 – 1876), 20 January, p. 2, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article111157544

[15] 1870 ‘EXTRAORDINARY CHARGE OF KIDNAPPING.’, Launceston Examiner (Tas. : 1842 – 1899), 18 January, p. 1 Supplement: Supplement to the Launceston Examiner., viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article39672820

[16] 1870 ‘THE LOUNGER.’, Launceston Examiner (Tas. : 1842 – 1899), 22 January, p. 4, viewed 17 August, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article39672894

[17] Roger Mayne, a descendent of Louisa Coventry and Henry Neilson said that this was how his grandmother described James’ appearance at Latrobe in the 1860s.

Hallo, my name is Lorraine McNeair, nee Coventry, and I have some information which may help you – or not.

Thanks Lorraine, look forward to hearing more. Cheers, Lynne

Lyn, you say that John Coventry arrived aboard the Moffat. Where did he land, and where did he embark from?

Hi Lorraine, the John Coventry who arrived aboard the Moffatt departed Woolwich on 27 October 1837, arriving in VDL. Records are accessible here: https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=John&qu=Coventry

Oh my gosh. I was just trying to find out what happened to Richard Hutchenson. Now I know!

A bit gruesome unfortunately 😦

Pingback: The First and Second Fleets | Lynne's Family

hi Lynne – could Mary Ann Beatley/Beatly/Bentley nee Martin have married Francis (Edge) Cox, son of Francis Cox and Sarah Edge ?

Yes, I think that’s right Kerrie.

Or it could be Mary Ann Cox using an earlier name. I’ll need to check my notes when I’m back home.